Volume 25, Issue 96 (3-2025)

refahj 2025, 25(96): 275-304 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Azimi A, Pir ahari N, Parnian S. (2025). Investigation and comparative analysis of social hope among Tehrani citizens. refahj. 25(96), : 10 doi:10.32598/refahj.25.96.4463.1

URL: http://refahj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-4319-en.html

URL: http://refahj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-4319-en.html

Keywords: Citizens of Tehran, Economic, Political, and Individual, Social Dimensions, Social Hope, Validation.

Full-Text [PDF 472 kb]

(987 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2311 Views)

Full-Text: (603 Views)

Extended abstract

Introduction

Hope serves as a foundational catalyst for human agency and societal advancement. When individuals perceive a viable future for their community, their lived experiences become imbued with innovation, purpose, and collective initiative (Snyder, 2002). Social hope, conceptualized as the intersubjective framework shaping communal aspirations, operates as both a barometer and driver of societal resilience. Khaniki (2019) posits that social hope enables societies to navigate crises by fostering cohesion between citizens and institutional structures, thereby aligning individual agency with systemic goals. This synergy not only amplifies civic engagement but also enhances the efficacy of policy implementation.

In Tehran, Iran’s socio-politically complex capital, pervasive crises—environmental degradation, eroding social capital, geopolitical instability, addiction, poverty, and systemic discrimination (Fazeli, 2018)—have precipitated a palpable decline in collective hope. Such conditions necessitate an urgent inquiry: What indicators define social hope within Tehran’s ethnically diverse population, and how might these inform interventions to mitigate societal despair?

This study distinguishes itself through its focus on social hope—rather than narrower constructs like “future-oriented hope” or “life satisfaction”—as a multidimensional phenomenon. By examining Tehran’s heterogeneous populace (encompassing varied ethnic, socioeconomic, and cultural strata), the research adopts a sociological lens to map how structural inequities and intersubjective perceptions interact to shape collective aspirations. This approach addresses a critical gap in extant literature, which often isolates psychological or demographic variables without accounting for the interplay of macro-level crises and micro-level lived experiences.

Conceptual Framework

“Hope” is the key to successful psychotherapy (Frank, 1968), has formed the basis of a type of psychotherapy (Frankel, 1984). Hope for the future and its opposite, despair, are among the important research subjects of sociologists, psychologists, and political scientists in the last decade (Safarishali & Tavvafi, 2018).

Recent sociological thinkers concerned about categories such as “hope”, “fear”, and social anxiety because the main assumption of sociologists in contemporary society is to recognize the connection between hope and social health (Farokhnezhadkeshki, 2017). Henri Desroche (1979), in his book “Sociology of Hope”, he has studied the trends of Utopianism for the first time.

Fazeli (2016) believes that recent conversations about hope in Iran indicate that there is a specific social situation in which hope has become a societal issue.

These theories are summarized in Table 1.

Source: (Tocqueville, 2017), (Peters, 1993), (Dahrendorf, 1976)Hope, and Progress (Eleanor Rathbone Memorial Lecture, (Bauman, 2004), (Durkheim, 2002), (Swedberg & Miyazaki, 2017), (Weber, 1994), (Turner, 2018), (Braithwaite, 2004), (McCormick, 2017).

Method

The present study is quantitative, using a survey method with a questionnaire. The validity of the questionnaire was calculated through content and face validity with the CVR tool. The total mean was 0.798, which indicates the validity of the tool. In addition to content validation, construct validation was also used for social hope. Cronbach’s alpha was also used for reliability (0.88), indicating the reliability of the tool. The statistical population of the study includes citizens of Tehran aged 15 to 65. Based on the Cochran formula, 384 people were determined as the sample size, and for reliability, this number was increased to 400 samples. The sampling method in the present study was carried out in two stages in the winter of 1401. First, multi-stage cluster sampling was used, and then from among the selected areas, the responding citizens were selected using simple random sampling. Table 2 shows the sampling method in this study. It is worth mentioning that, using the block map of the Statistics Organization, the selection of areas in each region was random; that is, on average, each region has five areas. Two blocks were selected randomly in each area, the point of each block starts its southeast, and the units of each block were determined by using the inventory of all plaques. Based on the sample method, households were chosen and, in each household, eligible individuals were surveyed (due to their willingness). In the absence of individuals, next house was utilized as a replacement. Lastly, the responses were analyzed by SPSS software.

Research Findings:

The study sample comprised 400 participants, with a near-balanced gender distribution (52.5% female, 47.5% male). Demographic characteristics revealed a predominance of middle-aged cohorts: 30.5% aged 37–47 years, followed by 27–37 years (22%), 47–57 years (22.5%), and 25% in other age brackets. Educational attainment varied, with 27% holding a high school diploma as their highest qualification, 26.3% a bachelor’s degree, 26.8% a master’s degree, 5.3% post-diploma certifications, and 14.6% possessing a PhD or below-diploma credentials. Marital status skewed toward married individuals (60.3%), while 39.7% identified as single, divorced, or other. Employment status highlighted 52.5% as employed, 19.3% retired, 10% students, 9.5% unemployed, and 8.7% engaged in other activities. Ethnically, the sample was predominantly Fars (43.5%), followed by Azeri (21.3%), Kurdish, Lor, Gilak, and other groups (33.7%), with Baloch representing the smallest subset (1.5%). Monthly income distribution showed 47.2% earning 7–14 million Tomans (Iranian currency), 28.8% at 14–21 million, 15.2% below 7 million, and 8.8% exceeding 21 million.

Key metric averages (on a 0–100 scale unless specified) included social hope (40.18 ± 5.40), social trust (19.30 ± 3.01), social security (20.74 ± 2.96), feeling of weakness (18.06 ± 2.95), social inequality (23.70 ± 3.11), and life satisfaction (31.28 ± 5.52). Notably, social security and life satisfaction scores fell below the theoretical midpoint of the scale (25), while social inequality and feeling of weakness exceeded normative benchmarks, underscoring systemic disparities and perceived vulnerability within the population. These findings align with broader contextual challenges in Tehran, including economic precarity and eroded institutional trust, as identified in prior research (Fazeli, 2018).

Discussion:

The findings reveal a pronounced deficit in social trust (M = 19.30), social security (M = 20.74), and life satisfaction (M = 31.28), alongside elevated perceptions of social inequality (M = 23.70) and feelings of collective weakness (M = 18.06). These metrics, measured against theoretical midpoints, underscore systemic vulnerabilities within Tehran’s social fabric, corroborating Fazeli’s (2018) assertion that intersecting crises—economic precarity, environmental strain, and institutional distrust—erode communal resilience. The inverse relationship between social inequality and hope aligns with Khaniki’s (2019) framework, positing that systemic disparities destabilize the intersubjective foundations necessary for collective agency.

This study advances prior work by contextualizing social hope as a multidimensional construct shaped by macro-structural inequities (e.g., ethnic disparities among Gilak and Balouch groups) and micro-level lived experiences (e.g., income stratification). The notably low social hope score (40.18%) reflects a feedback loop wherein diminished institutional trust curtails civic engagement, further entrenching despair—a dynamic resonant with Giddens’ (1984) structuration theory, which emphasizes the recursive interplay of agency and constraint.

Ethical Considerations:

Authors’ Participation: All authors have participated in the preparation of this article with informed consent.

Funding: No direct financial support was received from any institution or organization for the preparation of this article.

Conflict of Interest: There was no conflict of interest between the authors in this article.

Compliance with the principles of research ethics:

This article complies with the research ethics codes, and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health with the code IR.USWR.REC.1400.238.

Bauman, Z. (2004), To Hope is Human. Tikkun, 19(6): 64-67. Link

Braithwaite, V. (2004), The Hope Process and Social Inclusion. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 592(1): 128-151. Link

Dahrendorf, R. (1976), Inequality, Hope, and Progress (Eleanor Rathbone Memorial Lecture). Liverpool, Liverpool University Press. Link

Durkheim, E. (2002), On the Division of Social Work (Trans. by B. Parham). Tehran, Nahr-e-Karzan. Link (in Persian)

Amirpanahi, M., Malmir, M., Shokriyani, M. (2016), Status Measurement of Social Hope in Iran. Social Work Research Paper, 3: 79-106. Link (in Persian)

Farokhnezhadkeshki, D., Mohammadi, A., & Haghighatian, M. (2018), Investigating the Sociological Factors Effective In the Hope for the Future of Tabriz Residents, Urban Sociological Studies, 8(29): 81-108. Link (in Persian)

Introduction

Hope serves as a foundational catalyst for human agency and societal advancement. When individuals perceive a viable future for their community, their lived experiences become imbued with innovation, purpose, and collective initiative (Snyder, 2002). Social hope, conceptualized as the intersubjective framework shaping communal aspirations, operates as both a barometer and driver of societal resilience. Khaniki (2019) posits that social hope enables societies to navigate crises by fostering cohesion between citizens and institutional structures, thereby aligning individual agency with systemic goals. This synergy not only amplifies civic engagement but also enhances the efficacy of policy implementation.

In Tehran, Iran’s socio-politically complex capital, pervasive crises—environmental degradation, eroding social capital, geopolitical instability, addiction, poverty, and systemic discrimination (Fazeli, 2018)—have precipitated a palpable decline in collective hope. Such conditions necessitate an urgent inquiry: What indicators define social hope within Tehran’s ethnically diverse population, and how might these inform interventions to mitigate societal despair?

This study distinguishes itself through its focus on social hope—rather than narrower constructs like “future-oriented hope” or “life satisfaction”—as a multidimensional phenomenon. By examining Tehran’s heterogeneous populace (encompassing varied ethnic, socioeconomic, and cultural strata), the research adopts a sociological lens to map how structural inequities and intersubjective perceptions interact to shape collective aspirations. This approach addresses a critical gap in extant literature, which often isolates psychological or demographic variables without accounting for the interplay of macro-level crises and micro-level lived experiences.

Conceptual Framework

“Hope” is the key to successful psychotherapy (Frank, 1968), has formed the basis of a type of psychotherapy (Frankel, 1984). Hope for the future and its opposite, despair, are among the important research subjects of sociologists, psychologists, and political scientists in the last decade (Safarishali & Tavvafi, 2018).

Recent sociological thinkers concerned about categories such as “hope”, “fear”, and social anxiety because the main assumption of sociologists in contemporary society is to recognize the connection between hope and social health (Farokhnezhadkeshki, 2017). Henri Desroche (1979), in his book “Sociology of Hope”, he has studied the trends of Utopianism for the first time.

Albert Gray (2011: 209-211) in his book “Sociology of Health and Illness” stated that after the theoretical developments in sociology, things like social hope became among the categories of attention of this discipline. According to Rorty (2011) who defined the construct of social hope, social hope is the efforts, planning, and cooperation of people in society to achieve a goal, whether success is achieved or not (Mirsepasi, 2009: 41). Attachments to huge projects of social change should improve people and the existing society; not based on an ideal model, but to the extent, that it can provide an honorable life for people.

Social hope is more than an emotional understanding of the current situation; it is a kind of awareness of society and the two-way relationship between the individual and the social system (Turner, 2018). The sociology of hope should focus on the interactive flow of the actor and the social system about the category of social hope (Amirpanahi et al., 2016).Fazeli (2016) believes that recent conversations about hope in Iran indicate that there is a specific social situation in which hope has become a societal issue.

These theories are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Several Theories of Social Hope

.jpg)

.jpg)

Source: (Tocqueville, 2017), (Peters, 1993), (Dahrendorf, 1976)Hope, and Progress (Eleanor Rathbone Memorial Lecture, (Bauman, 2004), (Durkheim, 2002), (Swedberg & Miyazaki, 2017), (Weber, 1994), (Turner, 2018), (Braithwaite, 2004), (McCormick, 2017).

Method

The present study is quantitative, using a survey method with a questionnaire. The validity of the questionnaire was calculated through content and face validity with the CVR tool. The total mean was 0.798, which indicates the validity of the tool. In addition to content validation, construct validation was also used for social hope. Cronbach’s alpha was also used for reliability (0.88), indicating the reliability of the tool. The statistical population of the study includes citizens of Tehran aged 15 to 65. Based on the Cochran formula, 384 people were determined as the sample size, and for reliability, this number was increased to 400 samples. The sampling method in the present study was carried out in two stages in the winter of 1401. First, multi-stage cluster sampling was used, and then from among the selected areas, the responding citizens were selected using simple random sampling. Table 2 shows the sampling method in this study. It is worth mentioning that, using the block map of the Statistics Organization, the selection of areas in each region was random; that is, on average, each region has five areas. Two blocks were selected randomly in each area, the point of each block starts its southeast, and the units of each block were determined by using the inventory of all plaques. Based on the sample method, households were chosen and, in each household, eligible individuals were surveyed (due to their willingness). In the absence of individuals, next house was utilized as a replacement. Lastly, the responses were analyzed by SPSS software.

Research Findings:

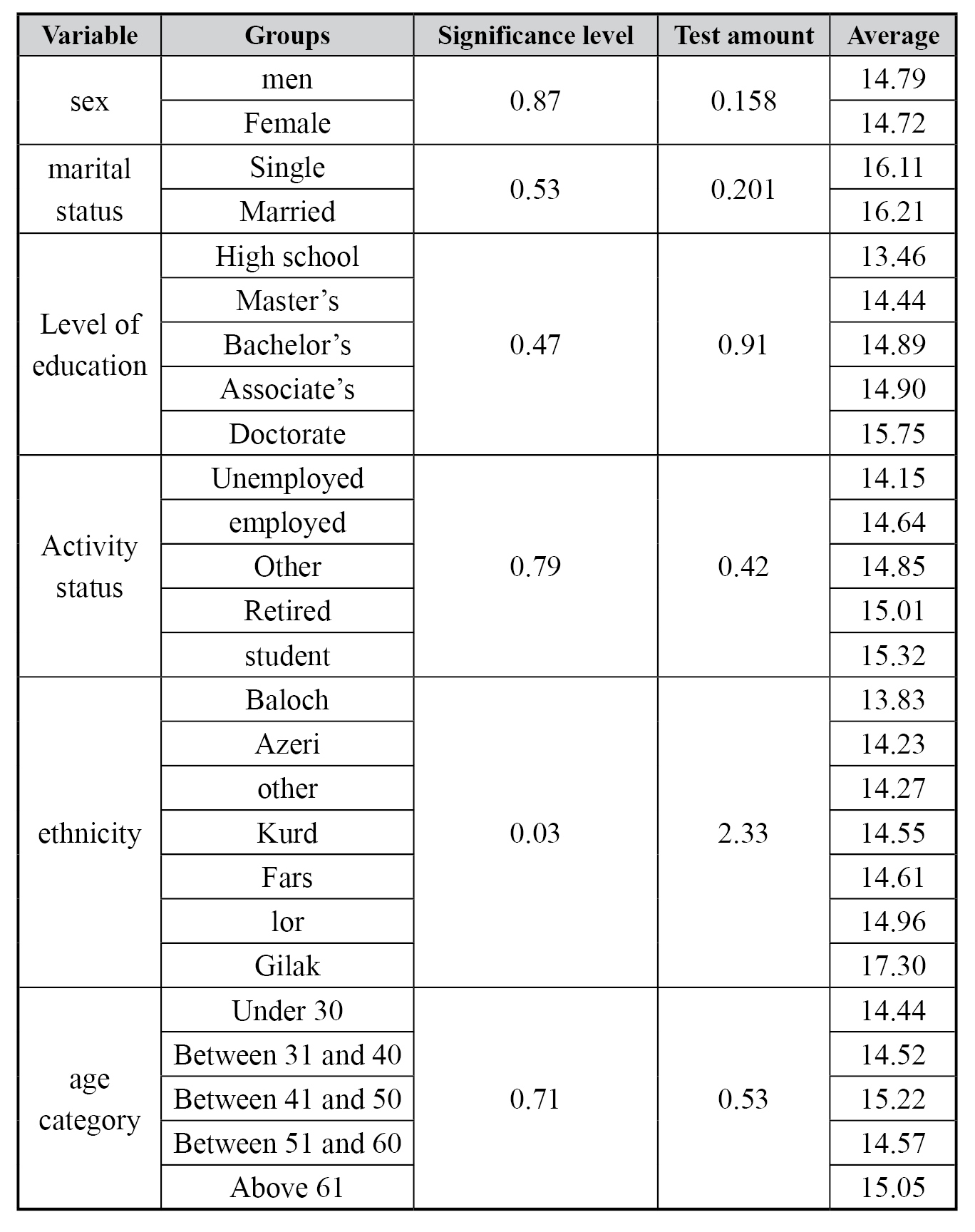

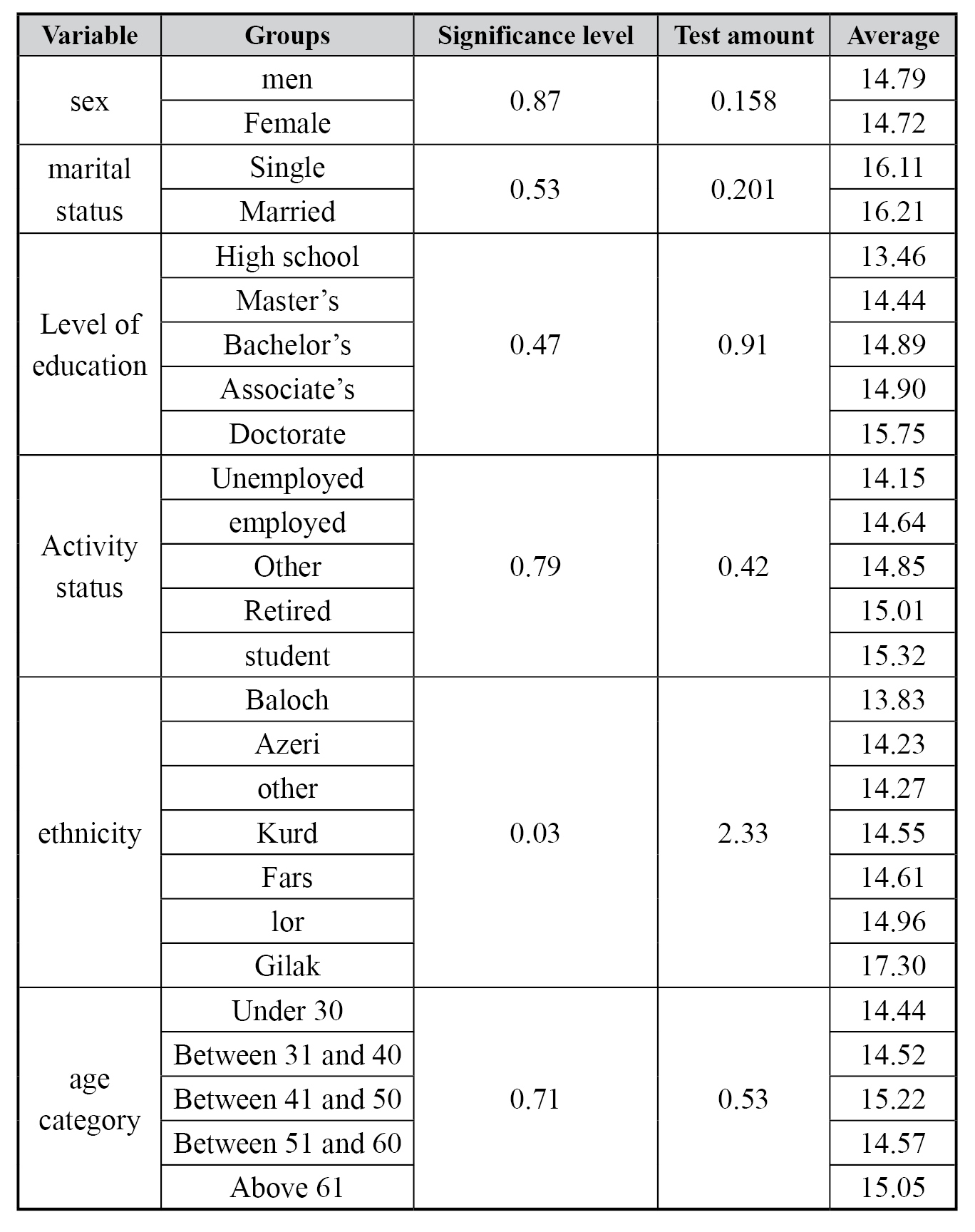

The study sample comprised 400 participants, with a near-balanced gender distribution (52.5% female, 47.5% male). Demographic characteristics revealed a predominance of middle-aged cohorts: 30.5% aged 37–47 years, followed by 27–37 years (22%), 47–57 years (22.5%), and 25% in other age brackets. Educational attainment varied, with 27% holding a high school diploma as their highest qualification, 26.3% a bachelor’s degree, 26.8% a master’s degree, 5.3% post-diploma certifications, and 14.6% possessing a PhD or below-diploma credentials. Marital status skewed toward married individuals (60.3%), while 39.7% identified as single, divorced, or other. Employment status highlighted 52.5% as employed, 19.3% retired, 10% students, 9.5% unemployed, and 8.7% engaged in other activities. Ethnically, the sample was predominantly Fars (43.5%), followed by Azeri (21.3%), Kurdish, Lor, Gilak, and other groups (33.7%), with Baloch representing the smallest subset (1.5%). Monthly income distribution showed 47.2% earning 7–14 million Tomans (Iranian currency), 28.8% at 14–21 million, 15.2% below 7 million, and 8.8% exceeding 21 million.

Key metric averages (on a 0–100 scale unless specified) included social hope (40.18 ± 5.40), social trust (19.30 ± 3.01), social security (20.74 ± 2.96), feeling of weakness (18.06 ± 2.95), social inequality (23.70 ± 3.11), and life satisfaction (31.28 ± 5.52). Notably, social security and life satisfaction scores fell below the theoretical midpoint of the scale (25), while social inequality and feeling of weakness exceeded normative benchmarks, underscoring systemic disparities and perceived vulnerability within the population. These findings align with broader contextual challenges in Tehran, including economic precarity and eroded institutional trust, as identified in prior research (Fazeli, 2018).

Discussion:

The findings reveal a pronounced deficit in social trust (M = 19.30), social security (M = 20.74), and life satisfaction (M = 31.28), alongside elevated perceptions of social inequality (M = 23.70) and feelings of collective weakness (M = 18.06). These metrics, measured against theoretical midpoints, underscore systemic vulnerabilities within Tehran’s social fabric, corroborating Fazeli’s (2018) assertion that intersecting crises—economic precarity, environmental strain, and institutional distrust—erode communal resilience. The inverse relationship between social inequality and hope aligns with Khaniki’s (2019) framework, positing that systemic disparities destabilize the intersubjective foundations necessary for collective agency.

This study advances prior work by contextualizing social hope as a multidimensional construct shaped by macro-structural inequities (e.g., ethnic disparities among Gilak and Balouch groups) and micro-level lived experiences (e.g., income stratification). The notably low social hope score (40.18%) reflects a feedback loop wherein diminished institutional trust curtails civic engagement, further entrenching despair—a dynamic resonant with Giddens’ (1984) structuration theory, which emphasizes the recursive interplay of agency and constraint.

Table 10. The Results of Independent Samples T-tests and One-Way Analysis of Variance

Ethical Considerations:

Authors’ Participation: All authors have participated in the preparation of this article with informed consent.

Funding: No direct financial support was received from any institution or organization for the preparation of this article.

Conflict of Interest: There was no conflict of interest between the authors in this article.

Compliance with the principles of research ethics:

This article complies with the research ethics codes, and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health with the code IR.USWR.REC.1400.238.

Bauman, Z. (2004), To Hope is Human. Tikkun, 19(6): 64-67. Link

Braithwaite, V. (2004), The Hope Process and Social Inclusion. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 592(1): 128-151. Link

Dahrendorf, R. (1976), Inequality, Hope, and Progress (Eleanor Rathbone Memorial Lecture). Liverpool, Liverpool University Press. Link

Durkheim, E. (2002), On the Division of Social Work (Trans. by B. Parham). Tehran, Nahr-e-Karzan. Link (in Persian)

Amirpanahi, M., Malmir, M., Shokriyani, M. (2016), Status Measurement of Social Hope in Iran. Social Work Research Paper, 3: 79-106. Link (in Persian)

Farokhnezhadkeshki, D., Mohammadi, A., & Haghighatian, M. (2018), Investigating the Sociological Factors Effective In the Hope for the Future of Tabriz Residents, Urban Sociological Studies, 8(29): 81-108. Link (in Persian)

Fazeli, M. (2019), the Social Hope of Humble Government and Small Successes. In H. Khaniki (Ed.), Social Hope; Nature, Condition and Etiology (557-562), Tehran, Research Institute of Cultural and Social Studies (in Cooperation with the Rahman Institute). Link (in Persian)

Fazeli, N. (2017), Contemporary Social Hope, Development of Social Science Education, 21(1). Link (in Persian)

Khaniki, H. (2019), Social Hope, the Nature, Status and Etiology, Tehran, Research Institute of Cultural and Social Studies (In Cooperation with the Rahman Institute). Link (in Persian)

McCormick, M. S. (2017). Rational Hope. Philosophical Explorations, 20(1): 127-141. Link

Mirsepasi, A. (2009). Ethics in the Public Domain, Tehran, Sales Publications. Link (in Persian)

Peters, C. H. (1993). Kant’s Philosophy of Hope, New York, Peter Lang Inc., International Academic Publishers. Link

Rorty, R. (2011), Social Philosophy and Hope (Translated by Azarang and Nader), Tehran, Nei Publication. Link (in Persian)

Safarishali, R., & Tavvafi, P. (2018). Investigating the Level of Hope for the Future and Factors Affecting It among Tehrani Citizens. Welfare and Social Development Planning Quarterly, 9(35): 117-157. Link (in Persian)

Stockdale, K. (2019). Social and Political Dimensions of Hope. Journal of Social Philosophy, 50(1): 28-44. Link

Swedberg, R., & Miyazaki, H. (2017). The Economy of Hope: An Introduction, Pennsylvania, University of Pennsylvania Press. Link

Taheridamneh, M., & Kazemi, M. (2020), A Futurist Reading of The Problematic of Social Hope in Iran. Quarterly Journal of Strategic Researches on Social Issues of Iran, 9(3): 49-80. Link (in Persian)

Tocqueville, A. D. (2017). Democracy in America. New York, Library of America. Link

Turner, J. H. (2018). Theoretical Principles of Sociology (Trans. by Ebrahimi Mirzei). Tehran, Loyeh Publication. Link (in Persian)

Weber, M. (1994). Weber: Political Writings. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Link

Fazeli, N. (2017), Contemporary Social Hope, Development of Social Science Education, 21(1). Link (in Persian)

Khaniki, H. (2019), Social Hope, the Nature, Status and Etiology, Tehran, Research Institute of Cultural and Social Studies (In Cooperation with the Rahman Institute). Link (in Persian)

McCormick, M. S. (2017). Rational Hope. Philosophical Explorations, 20(1): 127-141. Link

Mirsepasi, A. (2009). Ethics in the Public Domain, Tehran, Sales Publications. Link (in Persian)

Peters, C. H. (1993). Kant’s Philosophy of Hope, New York, Peter Lang Inc., International Academic Publishers. Link

Rorty, R. (2011), Social Philosophy and Hope (Translated by Azarang and Nader), Tehran, Nei Publication. Link (in Persian)

Safarishali, R., & Tavvafi, P. (2018). Investigating the Level of Hope for the Future and Factors Affecting It among Tehrani Citizens. Welfare and Social Development Planning Quarterly, 9(35): 117-157. Link (in Persian)

Stockdale, K. (2019). Social and Political Dimensions of Hope. Journal of Social Philosophy, 50(1): 28-44. Link

Swedberg, R., & Miyazaki, H. (2017). The Economy of Hope: An Introduction, Pennsylvania, University of Pennsylvania Press. Link

Taheridamneh, M., & Kazemi, M. (2020), A Futurist Reading of The Problematic of Social Hope in Iran. Quarterly Journal of Strategic Researches on Social Issues of Iran, 9(3): 49-80. Link (in Persian)

Tocqueville, A. D. (2017). Democracy in America. New York, Library of America. Link

Turner, J. H. (2018). Theoretical Principles of Sociology (Trans. by Ebrahimi Mirzei). Tehran, Loyeh Publication. Link (in Persian)

Weber, M. (1994). Weber: Political Writings. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Link

Type of Study: orginal |

Received: 2024/03/7 | Accepted: 2024/11/20 | Published: 2025/04/4

Received: 2024/03/7 | Accepted: 2024/11/20 | Published: 2025/04/4

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |